Of course, one man’s “works great†might be another man’s “don’t even try itâ€!

So I’m starting this topic with some examples from my own experience, and then we can discuss such things, and “speed up the learning curve†– specially for new builders.

Things that work well

Cable steering

Many racers out here on the West Coast have been using cable steering “foreverâ€, but I had to be contrarian and use rack-n-pinions and tillers. Until… the Beach Party Buggy arrived. This vehicle was built with fabulous craftsmanship by professional fabricators, but they were not vehicle dynamics engineers. I converted the Buggy from four wheels with no suspension to three wheels (which needs no suspension). Once the front fork was mounted, it was obvious that this was the perfect opportunity to try steering by steel cables. I installed a pulley on top of the front fork, and a hand crank between the front seats. Such an arrangement needs a lot of “gearingâ€, so the pulley up front is something like 9 inches in diameter, and there is no pulley at all on the hand crank – just the ¾ inch shaft itself. And it still could use more reduction. Many racers use a bicycle rim for the pulley.

Installing this, the cable needed to be wrapped many times around the shaft, and I tried to wrap it in a tight orderly spiral. But this cable was too stiff, and I wound up happy that the cable stayed on the shaft at all while I tightened the turnbuckle. I left it on the loose side, because the cable would obviously be “tripping over itself†when I turned the handle.

Guess what…? It worked great, right off the bat! The cable is slowly being chewed apart where it goes thru the hole in the shaft, but this can be easily monitored and the cable replaced as needed. The slack I allow in the cable so it can wrap over itself on the shaft without over-tightening causes no trouble at our low speeds.

Before, with four tiny wheels and wonky steering:

After, with three larger wheels and cable steering:

Independent drives

Many racers use differentials on their drive axles. And, mounted correctly and not overloaded, they can do the job. But they have the drawback of allowing one wheel to spin, while the other does nothing. (That why many of us like to have “PosiTraction†on our cars and trucks.) We have also seen that novice builders often fail to mount differentials correctly, and they soon break. So I’m very much in favor of independent drives. That means, no mechanical connection between the left and right drive wheels. The riders on the left drive the wheel on the left, and same on the right. This also helps with turning in mud and sand.

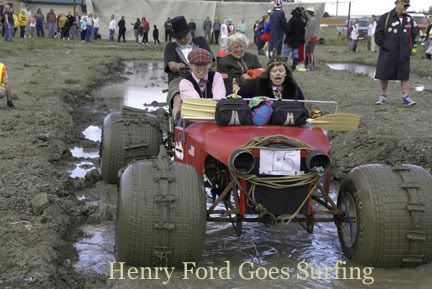

This “4x4†version of Henry Ford Goes Surfing worked very well. Four riders, each powering one wheel. Steering is by center articulation, which eliminates wheel alignment issues. Yes, I’m steering from the back seat – the parts just happened to fit best that way.

Tall wheels

There is no substitute for tall wheels. Basically, taller is better. It doesn’t matter much on pavement, but boy-howdy it makes a big difference in mud and sand.

This was my first KSR effort. The front wheel is eight feet tall, the rears six feet. It rolled over curbs and exposed railroad tracks like they were not there.

All wheel drive

In rough terrain, wheels that are not driving you forward are holding you back.

“Henry†again, with mud cleats strapped onto all four wheels. To my own surprise, we made it thru the Dismal Bog in Port Townsend, even with modest muscle power. ALL the power went to propelling us forward.

Lots of chain wrap

Chain wrap is how we describe how much of the sprocket is in contact with its chain. Quite simply, more is better. Chain wrap is the key factor in keeping the chain from skipping over the sprocket. Any less than close to 180 degrees of wrap is an invitation to skipping. Install fixed idlers (on the slack side of possible) if you need to increase chain wrap.

Triangulation

Finally, the most basic element of structural integrity -- triangulation. Sure, you can build with material that is stout enough to do the job by itself, but if you are building anything like a box or truss with small tubing, you should make sure there are no rectangular sections. All you need to see this for yourself are four pencils and some adhesive tape. Lay out a rectangle, and you can change its shape. But lay out a triangle, and it cannot take any other shape.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Now some Things that work poorly

Four wheels with no suspension

Ever been in an old house with warped floors, and a four-legged table teetered back and forth? Same with vehicles. A four-wheeled vehicle without suspension works well only on a flat surface. Scroll back up and look again at “Henry†coming down a sand dune. Notice that the terrain forces the vehicle to twist quite a bit. This vehicle happens to have suspension by center articulation, but one way or another you should have a mechanism that allows all four wheels to follow the terrain.

Lots of force on a differential

I mentioned earlier that a differential on a drive axle can work fine, but the lawn tractor and go-kart type of differentials that we usually get hold of are only so strong. The Counterfeit Bluesmobile…

…has the biggest diff I have seen in the sport, yet it detonated in the Dismal Bog. I had provided very low gearing, for four very strong riders. Bang! The diff housing split in two.

Floatation under the middle

I’ve seen some fabulous capsizings. (Regrettably, I lost the pictures in a computer crash.) You can have some of your water floatation under the vehicle, but you must have plenty of it outboard so you cannot tip over.

Lack of freewheels

If you are connecting two or more riders, you may think that they can synchronize their pedaling. Yes, tandem bicycle riders often do this, but it takes a lot of practice. In a one-shot deal like a KSR, with assorted untrained riders, forgettaboutit. I watched a rider get a seven-stitch gash in the back of his leg when the man behind him started pedaling before the man in front was ready. I’ve tried riding such a machine, and most of the energy went to “fighting†each other and failing to get synchronized. And we often need to take a short break from pedaling. So each rider must have his own freewheel.

All right…. Your turn.